Xtext relies heavily on EMF internally, but it can also be used as the serialization back-end of other EMF-based tools. In this section we introduce the basic concepts of the Eclipse Modeling Framework (EMF) in the context of Xtext. If you want to learn more about EMF, we recommend reading the EMF book.

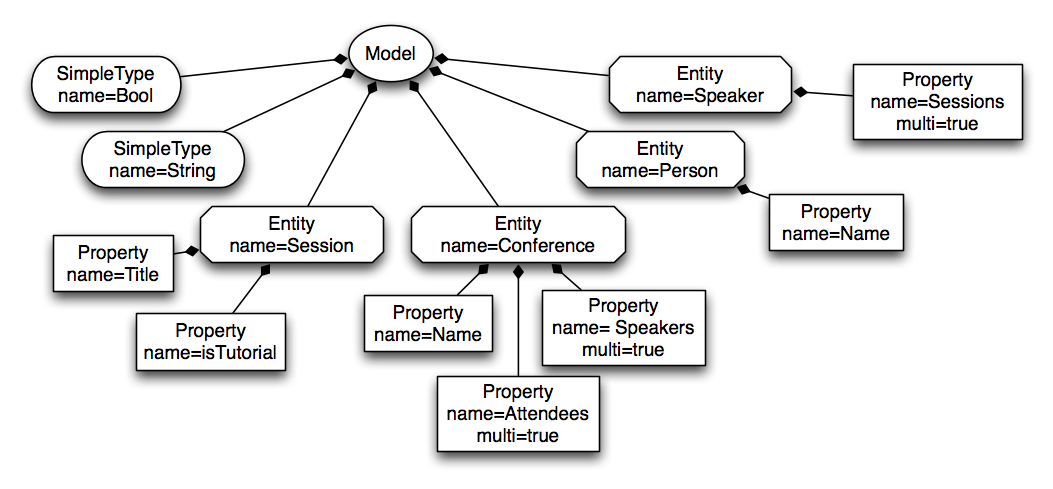

Xtext uses EMF models as the in-memory representation of any parsed text files. This in-memory object graph is called the abstract syntax tree (AST). Depending on the community this concepts is also called document object model (DOM), semantic model, or simply model. We use model and AST interchangeably. Given the example model from the domainmodel tutorial, the AST looks similar to this

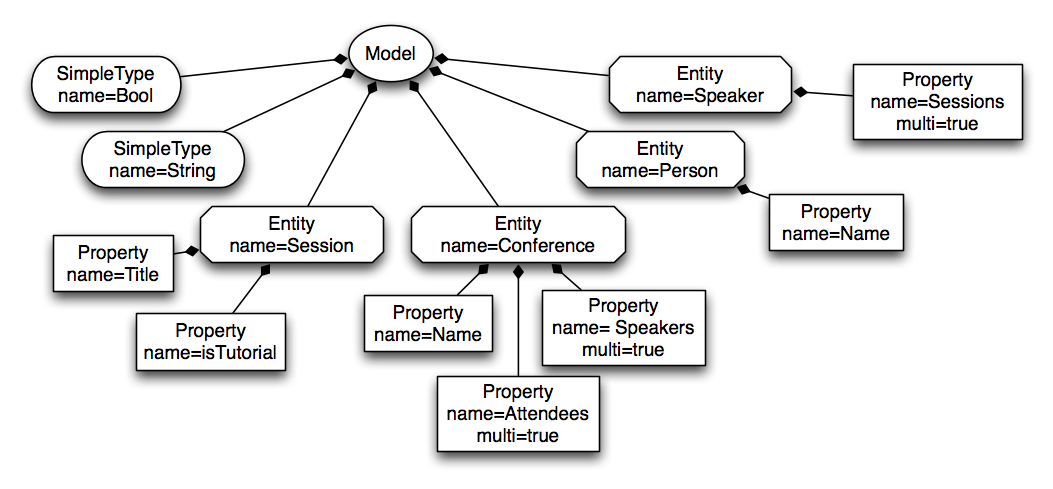

The AST should contain the essence of your textual models. It abstracts over syntactical information. It is used by later processing steps, such as validation, compilation or interpretation. In EMF a model is made up of instances of EObjects which are connected. An EObject is an instance of an EClass. A set of EClasses can be contained in a so called EPackage, which are both concepts of Ecore. In Xtext, meta-models are either inferred from the grammar or predefined by the user (see the section on EPackage declarations for details). The next diagram shows the meta-model of our example:

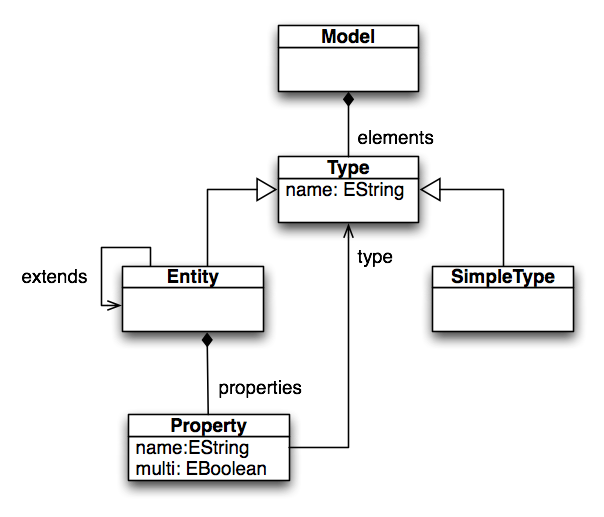

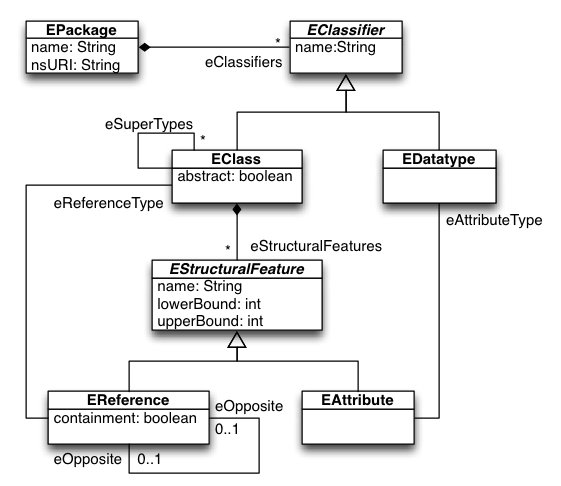

The language in which the meta-model is defined is called Ecore. In other words, the meta-model is the Ecore model of your language. Ecore is an essential part of EMF. Your models instantiate the meta-model, and your meta-model instantiates Ecore. To put an end to this recursion, Ecore is defined in itself (an instance of itself).

The meta-model defines the types of the semantic nodes as Ecore EClasses. EClasses are shown as boxes in the meta-model diagram, so in our example, Model, Type, SimpleType, Entity, and Property are EClasses. An EClass can inherit from other EClasses. Multiple inheritance is allowed in Ecore, but of course cycles are forbidden.

EClasses can have EAttributes for their simple properties. These are shown inside the EClasses nodes. The example contains two EAttributes name and one EAttribute multi. The domain of values for an EAttribute is defined by its EDataType. Ecore ships with some predefined EDataTypes, which essentially refer to Java primitive types and other immutable classes like String. To make a distinction from the Java types, the EDataTypes are prefixed with an E. In our example, that is EString and EBoolean.

In contrast to EAttributes, EReferences point to other EClasses. The containment flag indicates whether an EReference is a containment reference or a cross-reference. In the diagram, references are edges and containment references are marked with a diamond. At the model level, each element can have at most one container, i.e. another element referring to it with a containment reference. This infers a tree structure to the models, as can be seen in the sample model diagram. On the other hand, cross-references refer to elements that can be contained anywhere else. In the example, elements and properties are containment references, while type and extends are cross-references. For reasons of readability, we skipped the cross-references in the sample model diagram. Note that in contrast to other parser generators, Xtext creates ASTs with linked cross-references.

Other than associations in UML, EReferences in Ecore are always owned by one EClass and only navigable in the direction form the owner to the type. Bi-directional associations must be modeled as two references, being eOpposite of each other and owned by one end of the associations.

The superclass of EAttributes and EReferences is EStructuralFeature and allows to define a name and a cardinality by setting lowerBound and upperBound. Setting the latter to -1 means ‘unbounded’.

The common super type of EDataType and EClass is EClassifier. An EPackage acts as a namespace and container of EClassifiers.

We have summarized these most relevant concepts of Ecore in the following diagram:

EMF also ships with a code generator that generates Java classes from your Ecore model. The code generators input is the so called EMF generator model. It decorates (references) the Ecore model and adds additional information for the Ecore → Java transformation. Xtext will automatically generate a generator model with reasonable defaults for all generated meta-models, and run the EMF code generator on them.

The generated classes are based on the EMF runtime library, which offers a lot of infrastructure and tools to work with your models, such as persistence, reflection, referential integrity, lazy loading etc.

Among other things, the code generator will generate

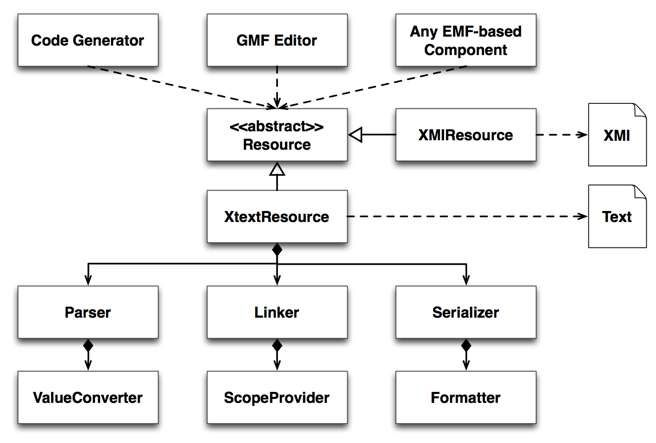

Xtext provides an implementation of EMF’s resource, the XtextResource. This does not only encapsulate the parser that converts text to an EMF model but also the serializer working the opposite direction. That way, an Xtext model just looks like any other Ecore-based model from the outside, making it amenable for the use by other EMF based tools. So in the ideal case, you can switch the serialization format of your models to your self-defined DSL by just replacing the resource implementation used by your other modeling tools.

The generator fragment ResourceFactoryFragment2 registers a factory for the XtextResource to EMF’s resource factory registry, such that all tools using the default mechanism to resolve a resource implementation will automatically get that resource implementation.

Using a self-defined textual syntax as the primary storage format has a number of advantages over the default XMI serialization, e.g.

Xtext targets easy to use and naturally feeling languages. It focuses on the lexical aspects of a language a bit more than on the semantic ones. As a consequence, a referenced Ecore model can contain more concepts than are actually covered by the Xtext grammar. As a result, not everything that is possibly expressed in the EMF model can be serialized back into a textual representation with regards to the grammar. So if you want to use Xtext to serialize your models as described above, it is good to have a couple of things in mind:

In some cases you may want to be able to reference an EObject of an Xtext model from another EMF artifact that is not managed by Xtext. In those cases URIs are used, which are made up of a part identifying the resource and a second part that points to an object. Each EObject contained in a resource can be identified by a so called fragment.

A fragment is a part of an EMF URI and needs to be unique per resource.

The generic resource shipped with EMF provides a generic path-like computation of fragments. These fragment paths are unique by default and do not have to be serialized. On the other hand, they can be easily broken by reordering the elements in a resource.

With an XMI or other binary-like serialization it is also common and possible to use UUIDs. UUIDs are usually binary and technical, so you don’t want to deal with them in human readable representations.

However with a textual concrete syntax we want to be able to compute fragments out of the human readable information. We don’t want to force people to use UUIDs (i.e. synthetic identifiers) or fragile, relative, generic paths in order to refer to EObjects.

Therefore one can contribute an IFragmentProvider per language. It has two methods: getFragment(EObject, Fallback) to calculate the fragment of an EObject and getEObject(Resource, String, Fallback) to go the opposite direction. The Fallback interface allows to delegate to the default strategy - which usually uses the fragment paths described above.

The following snippet shows how to use qualified names as fragments:

public QualifiedNameFragmentProvider implements IFragmentProvider {

@Inject

private IQualifiedNameProvider qualifiedNameProvider;

public String getFragment(EObject obj, Fallback fallback) {

String qName = qualifiedNameProvider.getQualifiedName(obj);

return qName != null ? qName : fallback.getFragment(obj);

}

public EObject getEObject(Resource resource,

String fragment,

Fallback fallback) {

if (fragment != null) {

Iterator<EObject> i = EcoreUtil.getAllContents(resource, false);

while(i.hasNext()) {

EObject eObject = i.next();

String candidateFragment = (eObject.eIsProxy())

? ((InternalEObject) eObject).eProxyURI().fragment()

: getFragment(eObject, fallback);

if (fragment.equals(candidateFragment))

return eObject;

}

}

return fallback.getEObject(fragment);

}

}

For performance reasons it is usually a good idea to navigate the resource based on the fragment information instead of traversing it completely. If you know that your fragment is computed from qualified names and your model contains something like NamedElements, you should split your fragment into those parts and query the root elements, the children of the best match and so on.

Furthermore it’s a good idea to have some kind of conflict resolution strategy to be able to distinguish between equally named elements that actually are different, e.g. properties may have the very same qualified name as entities.

We do no longer maintain the GMF example code and have removed it from our installation. You can still access the last version of the source code form our source code repository.

The Graphical Modeling Framework (GMF) allows to create graphical diagram editors for Ecore models. To illustrate how to build a GMF editor on top of an XtextResource we have provided an example. You must have the Helios version 2.3 of GMF Notation, Runtime and Tooling and their dependencies installed in your workbench to run the example. With other versions of GMF it might work to regenerate the diagram code.

The example consists of a number of plug-ins

| Plug-in | Framework | Purpose | Contents |

|---|---|---|---|

| o.e.x.example.gmf | Xtext | Xtext runtime plug-in | Grammar, derived metamodel and language infrastructure |

| o.e.x.e.g.ui | Xtext | Xtext UI plug-in | Xtext editor and services |

| o.e.x.e.g.edit | EMF | EMF.edit plug-in | UI services generated from the metamodel |

| o.e.x.e.g.models | GMF | GMF design models | Input for the GMF code generator |

| o.e.x.e.g.diagram | GMF | GMF diagram editor | Purely generated from the GMF design models |

| o.e.x.e.g.d.extensions | GMF and Xtext | GMF diagram editor extensions | Manual extensions to the generated GMF editor for integration with Xtext |

| o.e.x.gmf.glue | Xtext and GMF | Glue code | Generic code to integrate Xtext and GMF |

We will elaborate the example in three stages.

A diagram editor in GMF by default manages two resources: One for the semantic model, that is the model we’re actually interested in for further processing. In our example it is a model representing entities and data types. The second resource holds the notation model. It represents the shapes you see in the diagram and their graphical properties. Notation elements reference their semantic counterparts. An entity’s name would be in the semantic model, while the font to draw it in the diagram would be stored the notation model. Note that in the integration example we’re only trying to represent the semantic resource as text.

To keep the semantic model and the diagram model in sync, GMF uses a so called CanonicalEditPolicy. This component registers as a listener to the semantic model and automatically updates diagram elements when their semantic counterparts change, are added or are removed. Some notational information can be derived from the semantic model by some default mapping, but usually there is a lot of graphical stuff that the user wants to change to make the diagram look better.

In an Xtext editor, changes in the text are transferred to the underlying XtextResource by a call to the method XtextResource.update(int, int, String), which will trigger a partial parsing of the dirty text region and a replacement of the corresponding subtree in the AST model (semantic model).

Having an Xtext editor and a canonical GMF editor on the same resource can therefore lead to loss of notational information, as a change in the Xtext editor will remove a subtree in the AST, causing the CanonicalEditPolicy to remove all notational elements, even though it was customized by the user. Xtext rebuilds the AST and the notation model is restored using the default mapping. It is therefore not recommended to let an Xtext editor and a canonical GMF editor work on the same resource.

In this example, we let each editor use its own memory instance of the model and synchronize on file changes only. Both frameworks already synchronize with external changes to the edited files out-of-the-box. In the glue code, a org.eclipse.xtext.gmf.glue.concurrency.ConcurrentModificationObserver warns the user if he/she tries to edit the same file with two different model editors concurrently.

In the example, we started with writing an Xtext grammar for an entity language. As explained above, we preferred optional assignments and rather covered mandatory attributes later in a validator. Into the bargain, we added some services to improve the EMF integration, namely a formatter, a fragment provider and an unloader. Then we let Xtext generate the language infrastructure. From the derived Ecore model and its generator model, we generated the edit plug-in (needed by GMF) and added some fancier icons.

From the GMF side, we followed the default procedure and created a gmfgraph model, a gmftool model and a gmfmap model referring to the Ecore model derived form the Xtext grammar. We changed some settings in the gmfgen model derived by GMF from the gmfmap model, namely to enable printing and to enable validation and validation decorators. Then we generated the diagram editor.

Voilà, we now have a diagram editor that reads/writes its semantic model as text. Also note that the validator from Xtext is already integrated in the diagram editor via the menu bar.

GMF’s generated parser for the labels is a bit poor: It will work on attributes only, and will fail for cross-references, e.g. an attribute’s type. So why not use the Xtext parser to process the user’s input?

An XtextResource keeps track of it’s concrete syntax representation by means of a so called node model (see parser rules section for a more detailed description). The node model represents the parse tree and provides information on the offset, length and text that has been parsed to create a semantic model element. The nodes are attached to their semantic elements by means of a node adapter.

We can use the node adapter to access the text block that represents an attribute, and call the Xtext parser to parse the user input. The example code is contained in org.eclipse.xtext.gmf.glue.edit.part.AntlrParserWrapper. SimplePropertyWrapperEditPartOverride shows how this is integrated into the generated GMF editor. Use the EntitiesEditPartFactoryOverride to instantiate it and the EntitiesEditPartProviderOverride to create the overridden factory, and register the latter to the extension point. Note that this is a non-invasive way to extend the generated GMF editors.

When you test the editor, you will note that the node model will be corrupt after editing a few labels. This is because the node model is only updated by the Xtext parser and not by the serializer. So we need a way to automatically call the (partial) parser every time the semantic model is changed. You will find the required classes in the package org.eclipse.xtext.gmf.glue.editingdomain. To activate node model reconciling, you have to add a line

XtextNodeModelReconciler.adapt(editingDomain);

in the method createEditingDomain() of the generated EntitiesDocumentProvider. To avoid changing the generated code, you can modify the code generation template for that class by setting

Dynamic Templates -> true

Template Directory = "org.eclipse.xtext.example.gmf.models/templates"

in the GenEditorGenerator and

Required Plugins -> "org.eclipse.xtext.gmf.glue"

in the GenPlugin element of the gmfgen before generating the diagram editor anew.

SimplePropertyPopupXtextEditorEditPartOverride demonstrates how to spawn an Xtext editor to edit a model element. The editor pops up in its control and shows only the section of the selected element. It is a fully fledged Xtext editor, with support of validation, content assist and syntax highlighting. The edited text is only transferred back to the model if it does not have any errors.

Note that there still are synchronization issues, that’s why we keep this one marked as experimental.